Ballet Review: Nijinsky

Nijinsky

The Australian Ballet

Sydney Opera House

12 November 2016

Written by Deen Hamaker

In 1919, a broken Vaslav Nijinsky gave his final performance in the lobby of a Swiss hotel.

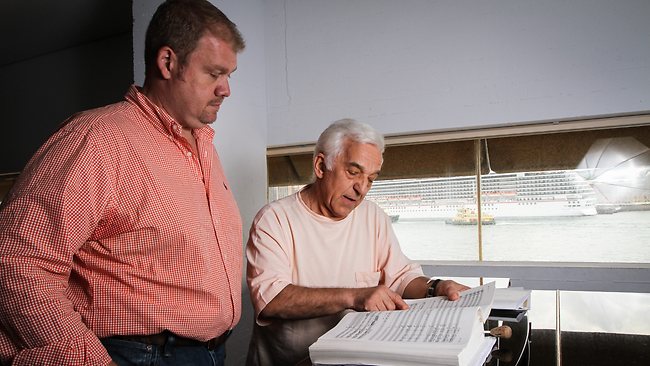

American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director John Neumeier has taken as his starting point, the recollections and thoughts that may have going through Nijinsky’s mind during that final performance. Neumeier has created a ballet that is a tribute to both the dancer and the visionary who changed the face of ballet forever.

Without shying away from the darkness of Nijinsky’s psyche, this stunning ballet reaches beyond Nijinsky’s dancing and choreographic work and into his relationships with his wife, his sister, Bronislava Nijinska, a brilliant choreographer in her own right, his brother Stanislav and his lover, the impresario behind the legendary Ballets Russes Serge Diaghliev.

More than a sum of excerpts of the most famous Ballets Russes pieces and beyond the obvious references to the specific Ballets Russes characters, choreographic language from Nijinsky’s ballets has been incorporated throughout the piece. Neumeier’s extensive knowledge of Nijinsky and his roles has helped him reference Nijinsky’s choreography without ever descending into a “party piece” gala.

With this season the Australian Ballet shows that it is more than a world class company – it is one of the very best ballet companies in the world today. The Australian Ballet is only the third company in the world to be granted the rights to dance this masterpiece. The entire ensemble is obviously loving the challenge of this endeavour. The ballet contains a large array of roles as well as spectacular ensembles for the corps de ballet. In this ballet about the man who created male dancing as we know it, it was the male ensemble that got to show off their chops with stunning evocations of Nijinsky’s dancing and what a sensational male corps the company has at the moment.

It is hard to think of what the arts would be like today without Serge Diaghliev and the Ballets Russes. In 1909 the Ballets Russes came from St Petersburg for a season in Paris and caused a sensation. The company’s performances sent a shockwave through the art world and made a huge impact. Music commissioned for the company includes Stravinsky’s Firebird, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring with Debussy’s Afternoon of the Faun. The set and costume designs of the Ballet Russes’ productions were legendary and made a huge impact on twentieth century art and design. Designers including Leon Bakst, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse lavishly designed of their productions. George Balanchine, Michel Fokine, Leonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska and Nijinsky himself created ballets for the company. Many of them form the cornerstone of the modern ballet repertoire.

At the centre of the Ballet Russes phenomenon was its star, the charismatic Vaslav Nijinsky. A titan of dance and a masterful, yet iconoclastic, choreographer, his shadow still looms large over all male dancers. His performances in Scheherazade, Petrushka, The Spectre of the Rose, Les Sylphides, Afternoon of the Faun, Jeux and The Blue God created fanaticism and are the stuff of legend. His choreography for The Rite of Spring caused a riot. He electrified audiences with his athletic vibrancy and frank sexuality. But it was only a brief moment in the spotlight. Today we have no film of Nijinsky dancing and the choreography of only one of Nijinsky’s ballets was notated. Based purely on photos, recollections and choreographic notes, this ballet is a stunning achievement that brings Nijinsky’s flawed genius and bravura dancing to life before our eyes.

Greeted with an open stage as we enter the theatre, it is a lovely surprise to see David McAllister, Artistic Director of the Australian Ballet, coming down the stairs leading a group of guests coming to Nijinsky’s final performance. Beginning with Nijinsky’s last performance in 1919, we are soon drawn into his fractured visions of his life. Characters from his most famous ballets appear and disappear, dancing fragments of their roles. Soon we are out of the hotel lobby and into the world of Scheherazade. The Golden Slave hangs in the air surrounded by harem girls. Just as quickly we move into a studio for a dynamic pas de deux for Nijinsky and Diaghliev. This is quickly followed by an extended pas de trois for Nijinsky, the Faun and his future wife Romola on the deck of a South America bound ship. The Faun, the most overtly sexual of all of Nijinsky’s characters, embodies the lust between the lovers.

The second act goes futher into Nijinsky’s psyche exploring the effect of the loss of his mentally ill brother and the darkness of the First World War. In one of the cleverest and most devastating moments, Petrushka, the tragic forlorn puppet, stripped of his colour in a black & white costume, becomes the embodiment of the tragic loss and violence of war. Nijinsky’s brother’s madness and death amongst the carnage of the war mirrors Nijinsky’s later madness. Stanislav is given some stunningly athletic choreography, executed tremendously by Brett Chynoweth.

Musically this production is a triumph. Three movements from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade provide colour and the perfect accompaniment to the Ballets Russes scenes. Shostakovich’s Sonata for Viola and Piano is used for the haunting lingering pas de deux for Nijinsky and Diaghliev. The second act is taken up by Shostakovich’s dark and brooding Symphony No. 11.

Nicolette Fraillon leads the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra with style and grace. The quiet moments, particularly those in the second act, are beautifully controlled and transcendent. Even the biggest and wildest moments are done with finesse. Obviously the orchestra was enjoying playing some music beyond their regular fare and it was a bravura performance by all.

In the lead role of Vaslav Nijinsky, Alexandre Riabko, a principal artist from the Hamburg Ballet, danced the fiendishly difficult role with intensity and dexterity. Riabko created the role of Nijinsky in Hamburg and he showed just how well he inhabits this enigmatic character. In this multi-faceted role, the choreography freely moves between contemporary movement, Nijinsky’s distinctive style and classical ballet. Riabko moved seamlessly between styles, his portrayal stunningly powerful and danced with immense feeling and conviction. Riabko was a sensation and the final moments are extraordinary.

In a huge cast full of character roles, the whole company was extraordinary. Natasha Kusch was fabulous as Nijinsky’s wife, Romola. Leanne Stojmenov was sensational as Bronislava Nijinska. Andrew Killian brought Diaghilev to life with style and just the right hint of menacing sexuality. Brett Chynoweth’s portrayal of Stanislav’s madness and despair was stunning and heartbreaking, as was Brett Simon’s wild frenetic dancing as Petrushka. Particular kudos goes to Jarryd Madden as the Faun and the Golden Slave and to Chengwu Guo as Harlequin and the Spirit of the Rose. Both handle the incredibly difficult bravura choreography with panache and dynamism.

To accompany his ballet, John Neumeier designed both the sets and the costumes based on the designs of Leon Bakst for the original Ballet Russes productions and they look spectacular. Particularly impressive are the costumes that evoke Nijinsky’s characters rather than being literal representations of the original costume designs. Ralf Merkel’s lighting design from a concept of Neumeier’s is stunningly effective. The sudden changes of mood and location are cleverly represented in both the colour and placement of the lighting. The quick set changes belie the inadequacies of the wingspace of the Joan Sutherland theatre. Congratulations must be made to an obviously hard working back stage crew who made it all magically happen in front of our eyes.

The Australian Ballet is legendary for their exceptional performances but with Nijinsky they have raised the bar beyond their previous heights. One hopes that audiences embrace this stunning ballet because it really deserves to become a part of the company’s ongoing repertoire.

Deen Hamaker for SoundsLikeSydney©

Deen Hamaker is a passionate opera aficionado and commentator. Introduced to theatre, opera and classical music at a very young age, he has acted in and directed several theatre productions, both in Australia and overseas. Deen lived in Japan for several years and studied the performing arts of Asia. Deen’s particular passion is opera, particularly the Russian, French and Modern repertoire. Deen was a contributing author for “Great, Grand and Famous Opera Houses”, 2012. Fluent in Japanese, Deen holds a Bachelor of Arts in Japanese from Griffith University and currently lives in Sydney.