Benjamin grosvenor ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ – a formidable talent

Playtime for a young Benjamin Grosvenor was less about manipulating a games console or donning mouthguard and shin pads. For him, ‘playtime’ meant time with his beloved piano – “the big shiny black thing in the music room – very exciting for a child”.

This fascination took him from starting pianos lessons aged 6, to winning the Keyboard Final of the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition in 2004, aged just eleven. Now, aged just 20, he is the youngest British musician to sign to Decca, and the first British pianist to join the label in almost 60 years. At his recent graduation from London’s Royal Academy of Music, Benjamin was awarded ‘The Queen’s Commendation for Excellence’, presented to the best all-round student of the year.

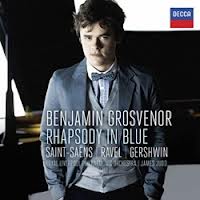

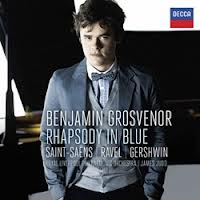

Benjamin Grosvenor was in Sydney recently to showcase his second CD under the Decca label, Rhapsody in Blue. Performed with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by James Judd, it features Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 2, Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major, and Gershwin’s classic from which the CD takes its title. “The idea”, says Grosvenor is to go from the French music of Saint-Saëns to Ravel’s jazz influenced French music – Ravel wrote the piece soon after he returned from America – completing the idea is jazz in the form of Gershwin – and there are little encore pieces between the concertos.” Having already recorded Chopin’s Four Scherzi and Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit for Decca, this is Grosvenor’s debut concerto recording.

The critics have been impressed. “Grosvenor, you can tell, is a Romantic pianist, almost from another age. He doesn’t deconstruct, or stand at a distance. He jumps inside the music’s soul” said The Times; and The Observer wrote: “Grosvenor’s balance of oratory and ornament, gesture and poetry … are moving as well as impressive.”

Cynics would dismiss him as a talent that will burn out too young. However, hearing him perform, it is evident that his is a formidable ability which presented itself early , that was recognised and sensitively nurtured. This also means that he was not pushed to shoulder repertoire that was too advanced for him, either technically or emotionally. He has been allowed to mature on his own terms. The present is glorious and the best is yet to come.

Speaking to Grosvenor during his recent Sydney visit, it was clear that music was at the centre of the Grosvenor household. Benjamin’s mother was a piano teacher had he had four older brothers. “She started us all on the piano from around the age of 6. She was teaching on it all the time so the piano was already very familiar to me. My brothers then took up trumpet, violin, guitar and clarinet but they all gave up in their early teens. They used to play together as family ensemble, but I was last on the scene so I didn’t really get involved in that.”

Reassuringly, Benjamin Grosvenor admits “I didn’t have any inclination to practice at first – I was quite reluctant. I was spurred on to practice by competition because some friends at school started and I was afraid they would catch me up so that’s what gave me the impetus and I got to like it more.” The passion had been kindled; reluctance dissipated and even teenage rebellion was not on the agenda . The neighbours complained and the piano was moved to the further side of the room; boxes from the CD he cut when he was 15 were stashed in front of the chimney to create rudimentary sound proofing. These days, he says, the complaints have abated.

Benjamin Grosvenor went on to begin his tertiary level piano studies at London’s Royal Academy of Music when he was 16. Describing that experience, he says entering a prestigious tertiary institution in his mid-teens wasn’t daunting. “I’d already built up a connection with the academy. When I was 10 I started having lessons with Christopher Elton, the Head of Keyboard Studies and when I was 13, I started having weekly academic lessons in music theory. It was great to be around lots of people who were interested in the things that I was, to the same level. ”

Unusually gifted, Grosvenor was academically ready for secondary school aged 10. Realising he was to young emotionally, he stayed on at primary school and completed components of his GCSE early, eventually leaving school at 14 and undergoing home tuition till he entered the Royal Academy, happy to finally be immersed in his passion.

Unlike stringed instruments which can be adapted to the stature of the young learner, pianos don’t come in half sizes. This naturally limits the repertoire that can be played. ” When I started performing at the age of 10, I could already stretch an octave. Of course that expanded the repertoire that I could play. But all the time through my teenage years, I built up physically, as my repertoire became more technically demanding.”

By the time Grosvenor won the BBC Young Musician Award in 2004, he could stretch a 9th. ” I moved on to more tricky pieces quickly. The competition, which I entered when I was 10 really helped me to grow, because for every round I had to learn new repertoire that helped me to build and move onto more challenging pieces. I was the youngest in the competition by 4 or 5 years.

Whilst the piano was the heart of the Grosvenor home, as a cultural phenomenon, it seems that fewer 21st century homes have pianos; a good instrument takes up space, can be expensive to maintain and an increasing number of pianos are dumped.

We’re not being overly pessimistic. “It certainly is the case – it’s a shame because pianos can be obtained quite cheaply now. Not great ones of course – but great thing about a piano and the reason it is the centre of the home is that anyone can make a sound out of it – unlike the violin where you have to spend ages before you can get a decent note out of it, even an inexperienced player can get a good sound from it, so children have a great attraction to it. You can buy a piano as cheaply as a television now, and we have electric pianos which don’t have to be maintained.”

What advice would Benjamin Grosvenor give to parents contemplating a piano purchase? “A terrible instrument it wouldn’t help in control and production of sound. If they can’t get a good piano, a good electric instruments is quite suitable – I have one myself which I use if my Mum is teaching on my piano and it is good for certain kinds of work. The one I have has wooden keys, which makes the action heavier, like a grand piano. I can use it with headphones which means I can practice without disturbing anyone else.”

Grosvenor adds a note of caution. ” It’s not something I would practice on for extended period of time – it’s good for learning notes – but when I’m beginning to think in great detail about interpretation, pedalling and dynamics, I practice on a proper instrument.”

Grosvenor’s repertoire for his recitals and his CDs extends from JS Bach through Chopin, Liszt, Rachmanninov and Scriabin, to Saint-Saëns, Ravel and Gershwin. The Romantics, however, have always been his first love. “From a young age I was most interested in the music of the Romantic period but my tastes have broadened over time. My favourite composer was Chopin. I didn’t like Bach at all till I was 14. I’d only heard very dry academic readings of his music, until II heard a recording of the Well-Tempered Clavier by Samuel Feinberg, who used the piano to its full capability and really opened my mind to what Bach’s music could be. Beethoven is someone I became interested in later as well.”

Accustomed to being the youngest in the pack, and the exception rather than the norm, Grosvenor jokes that he was again, the youngest member by decades when he began to pursue his childhood interest in jazz, signing up to the Billy Mayerl Society, aged 9. Mayerl, an English composer of music in the jazz idiom, an influence that is reflected in his choice of jazz infused repertoire in concert and on CD.

Looking to the future, Grosvenor asserts that although he does have composers sending him music, there is no emerging British composer who stirs passion in him.

For now, the young pianist is content. ” I’m happy in this career. I’d like to sort out what I’m comfortable with as a schedule. I think eventually Id be interested in teaching. Conducting is something I’d like to study soon and turn to later in life.”

Benjamin Grosvenor was interviewed by Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney ©

Benjamin Grosvenor Rhapsody in Blue is out on the Decca label, catalogue number: 0289 478 3527 1