Concert Review: Elektra

Elektra

Sydney Symphony Orchestra

Sydney Opera House, Concert Hall

February 24

As a cathartic experience the Monday evening performance of Richard Strauss’s Elektra by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra would be difficult to surpass. Such was the emotional tension generated by the waves of sheer orchestral power and a dramatic soprano who is nothing short of a vocal phenomenon that the death of the eponymous heroine became inexorable and the only possible means of release.

It has to be said that the shock and awe generated by an orchestra of a hundred or so fine orchestral players, including a formidable lineup of brass, might have been uncomfortably overwhelming for some members of the audience, but from the middle of row M in the Circle it was beyond thrilling. Here was the Concert Hall being put to its originally intended use: the performance of opera; not that the conformation used for this production was envisaged by the architects. The orchestra was placed in the front stalls area, the singers at the front of the stage and eight members of the Sydney Dance Company on a raised platform behind the singers. Towards the end of the opera the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs made a brief appearance ranged along the upper sides of the auditorium.

Although it was advertised as a concert performance, there was considerable action on the part of the singers as well as the dancers. It was obvious that Christine Goerke is very much at home on the operatic stage with many performances as Elektra to her credit. From her first utterance, ‘Allein!’ / ‘Alone!’ it was obvious that this was a voice of singular richness and amplitude. Elektra’s first ‘aria’ is almost ten minutes of impassioned outpourings culminating in a top C towards the end. For ease of production and variation of emotional colour it is difficult to imagine that any dramatic soprano of such power throughout her extensive vocal range could impress more thoroughly. Furthermore, Goerke’s voice maintained its beauty, never once being compromised into a shriek. Any reputed use of amplification was totally ignored by Goerke, who surely needed none at all. She filled the hall irrespective of her position on the stage. She prowled around, lounged on the rostrum, mounted a rather precarious looking bench and generally threw herself into the part, including the final stamping and swaying as she called others to join her in a dance of ecstatic delirium.

Other singers gave of their best both vocally and dramatically. Lisa Gasteen, dressed as a resplendent, glittering Queen Klytemnestra made a compelling nightmare-plagued murderer of her husband Agamemnon. Her vacillation between fear and loathing of her vengeful daughter and the need for her reassurance was focused and chilling. Gasteen’s concentrated vocal power, especially in her lower register, infused just the right quality of menace into the role.

Elektra requires three female singers of the highest calibre and Cheryl Barker provided the third of these. Adding to a string of highly acclaimed Strauss roles, her portrayal of Chrysothemis, Elektra’s conventional sister who is more interested in acquiring a husband and children than bloody revenge, provided a foil to the histrionics of her mother and sister. With soaring, lyrical upper notes, her voice and feminine appeal acted as a striking contrast. There was also commendable singing from the Maids, with a particularly engaging Lee Abrahmsen as the sympathetic Fifth Maid.

Although the male roles are shorter and mostly more peripheral, they are important. With the exception of Kim Begley’s ringing Aegisthus, however, the male singers tended to be over-shadowed by the orchestral forces, particularly the richly toned brass. Nevertheless, Peter Coleman-Wright’s portrayal of Orestes was given additional impact by his musical intelligence and strong sense of theatre. The emotional recognition scene between Elektra and her brother, whom she believed to be dead, was just as affecting as any fully staged treatment would have provided.

Apart from the complexity of the drama and the music, certain aspects of the staging taxed the attention of the audience. A translation of Hofmannsthal’s wordy libretto was displayed as indispensable surtitles, but did compete with the actions of the singers and the dancing. Fortunately, key moments in the opera were not accompanied by dance sequences, so the audience could just concentrate on the music and the interplay between the characters. It was difficult to understand the logic behind when the dancers appeared, but it seemed to be more in the group scenes and the orchestral passages. Their presence in Elektra’s final dance was predictable. Dressed in various shades of blue, the dancers reflected the mood of a scene rather than rendering it literally, although there were some fairly literal movements at times. Whether a distraction or an enhancement, there is no doubt that the dancers were accomplished and Stephanie Lake’s choreography thoughtfully constructed. As an animated background texture it did serve to complement aspects of the drama. It is perhaps ironic that later in life Hofmannsthal himself acknowledged the limitations of text and a preference for the purer expressive form of gesture and dance. Perhaps this acts as a justification for the inclusion of the dance component. At least the judicious and sometimes highly dramatic lighting design by Toby Sewell was an unequivocally positive addition.

This is the only time that I have ever gone to the expense of flying interstate to hear a performance. The combination of Christine Goerke, Lisa Gasteen and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in this riveting work proved an irresistible attraction. So, was it worth it? Without a doubt. My only regret is that I missed hearing the first of the two performances. Christine Goerke is a singer of such extraordinary powers that any opportunity to hear her should be embraced.

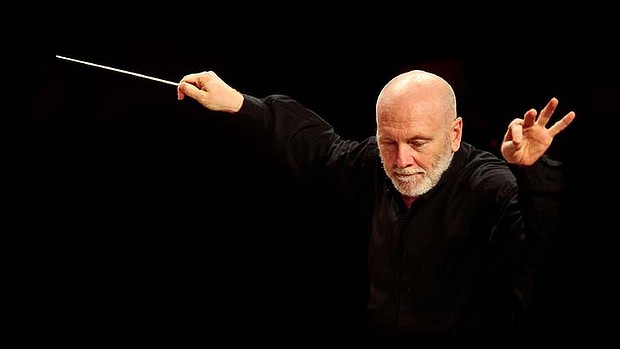

As for the orchestra, under the baton of newly appointed Chief Conductor David Robertson, the full gamut of sound was on display. From the more delicate, lightly scored passages to those reverberating with full orchestral might, all were marked by an elasticity that delineated the heights and depths of Greek tragedy at its most elemental. No wonder Elektra felt herself buried under the weight of an ocean by the end of the opera.

Even given its overload on the senses, this performance of Elektra, was an experience to treasure. As a couple of notable gentlemen (namely Shakespeare and Richard Gill) have directed, ‘Give me excess of it!’.

Heather Leviston for SoundsLikeSydney©

Heather Leviston has devoted much of her life to listening to classical music and attending concerts. An addiction to vocal and string music has led her to undertake extensive training in singing and perform as a member of the Victoria State Opera chorus and as a soloist with various musical organisations. As a founding academic teacher of the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School, she has had the privilege of witnessing the progress of many talented students, keenly following their careers by attending their performances both in Australia and overseas. As a reviewer, recently for artsHub, she has been keen to bring attention to the fine music-making that is on offer in Australia, especially in the form of live performance.