Concert Review: Schubert Immersion Weekend / Seraphim Trio

Seraphim Trio: Helen Ayres (violin), Anna Goldsworthy (piano), Tim Nankervis (cello)

With Jacqui Cronin (viola), David Campbell (double bass)

10-11 September 2016, The Independent Theatre, North Sydney

Written by Larry Turner

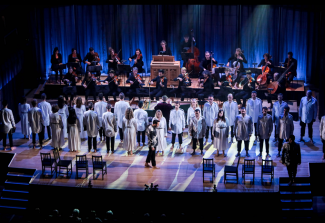

The Seraphim Trio has nominated 2016 as ‘our year of total immersion in Schubert’. This culminated in a splendid weekend when they presented all of Schubert’s chamber music for strings and piano in the Independent Theatre, North Sydney. This is an excellent venue for chamber music with a quite intimate feeling and an acoustic that is clear but with an attractively warm bloom.

Over the two afternoons the Seraphim Trio demonstrated its long familiarity with Schubert’s works. They displayed excellent rapport and a consummate sense of ensemble with unanimity of phrasing and finely judged balance. Individually, each of the three players made an excellent contribution. Helen Ayres led the ensemble strongly, firmly establishing the feeling for each movement and its structure. Cellist Tim Nankervis provided a fine bass foundation for the ensemble with warm tone and sensitive phrasing. Anna Goldsworthy’s delicately poised piano playing was a continuing delight throughout.

The Saturday afternoon recital presented the two massive piano trios dating from Schubert’s final years. They are both expansive works encompassing a wide range of emotions. Helen Ayres’s assured violin playing launched the Trio in B flat, D. 898 and established a sense of embarking on an epic journey. There were also many opportunities to enjoy Anna Goldsworthy’s finely controlled playing. This ranged from long floating lines with subtle rubato to vigorous responses in the robust dialogues with the other instruments. She was clearly enjoying Schubert’s magical piano writing and her enjoyment communicated itself to the audience. In the slow movement the cello has numerous solo opportunities and Tim Nankervis projected the legato dream-like passages with a warm, full tone. The contrasting scherzo was nicely characterised and in the jaunty finale the sense of fun was underlined.

The second work in the Saturday concert was the Trio in E flat, D. 929. This was one of Schubert’s last completed works and one of the few late chamber works that he actually heard performed. It contains even more poignant moments than the B flat Trio.

The playing in the opening movement established the atmosphere of mixed drama and reflection that is so characteristic of late Schubert. In the slow movement Tim Nankervis’s long cantabile cello lines were again projected with an attractively burnished sound. This movement has a real sense of laughter through tears such as prompted the observation by the tenor Ian Bostridge that Schubert’s music often becomes even more heart-wrenching when it moves from a minor key into a major one. The playing of the energetic scherzo provided a nice contrast of mood. The finale then returned to the arena of mixed emotions with its reminiscences of the haunting cello theme from the slow movement, again evocatively played by Tim Nankervis.

The recital on the Sunday afternoon was subtitled ‘Wanderer’ and this appropriately summarises many of Schubert’s long movements which seem to roam ever onward, but incorporate the most sublime moments en route. They are like rambling through the countryside, where familiar views are interspersed with unfamiliar scenes, often with disturbing side paths.

The first half of the recital on Sunday provided a brief compilation of works from Schubert’s early, middle and late career. It opened with the single movement Sonatensatz, written when he was only 15. The manuscript, which was rediscovered in 1922, is headed ‘Sonate’, suggesting it was intended as the first movement of a sonata which was never completed. Such an early work, naturally less complex than the later ones, is influenced by the elegance and classical restraint of Haydn which the performance brought out clearly.

Next came the delightful Notturno D.897 written the year before Schubert died. The contrast with the early Sonatensatz is huge – a striking illustration of how Schubert’s style matured in the intervening ten years. The Notturno was probably originally intended as the slow movement for the B flat string trio but discarded for some reason. In any case it stands very well on its own. The players nicely captured the delicate nocturnal atmosphere of the opening with wonderful delicacy in the piano playing. The stormy turmoil of the middle section is suggestive of anxieties felt at 3am in times of trouble. Particularly effective in this section was the close rapport between the violin and cello.

The first half of the concert concluded with a rare performance of the Adagio and Rondo Concertante D. 487 written in 1816. It is Schubert’s only work for piano quartet and is in just two linked movements. It features a prominent virtuoso piano part with the strings mostly relegated to supporting roles – although there was some very attractive lyrical violin playing from Helen Ayres. The spotlight, however, was on Anna Goldsworthy who certainly delivered the goods in a dazzling, well shaped performance.

After interval came the deservedly popular Trout Quintet D. 667 (voted number 1 in ABC-FM’s 2008 Classic 100 Chamber Music survey). This is Schubert at his most amiable and the performance captured the spirit of convivial music-making among friends. Unlike the conventional string quartet configuration the score calls for only a single violin and adds a double bass instead, which frees the cello to play a greater melodic role than usual. Tim Nankervis seized the opportunity for some lovely cantabile playing, especially in the famous variations movement. The double bass playing of David Campbell provided a solid bass foundation and he also demonstrated admirable delicacy and accuracy in florid passages. The part for the viola is not prominent. Jacqui Cronin played with an attractive, rounded tone, though it was somewhat recessed and could have been projected more strongly. The work’s unconventional scoring allows the piano to spend more time engaging in decorative embellishments in its upper octaves. Anna Goldsworthy’s execution of the virtuoso passages was often breathtaking while her filigree playing was even more delightful.

Liszt described Schubert as the most poetic musician who ever lived and after listening to his piano and strings chamber music for two afternoons it is difficult to disagree. Schubert’s music often seems to expresses what words cannot and the Seraphim Trio’s Immersion Weekend demonstrated this most convincingly.

Larry Turner for SoundsLikeSydney©

Larry Turner is an avid attender of concerts and operas and has been reviewing performances for Sounds Like Sydney for several years. As a chorister for many years in both Sydney and London, he particularly enjoys music from both the great a capella period and the baroque. He has written programme notes for Sydney Philharmonia, the Intervarsity Choral Festival and the Sydneian Bach Choir and is currently part of a team researching the history of Sydney Philharmonia for its forthcoming centenary.