Concert Review: The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge/Musica Viva

Concert Review: The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge

City Recital Hall, Sydney, Sunday July28, 2024

The Choir of Kings College Cambridge under its Director of Music, Daniel Hyde brings its centuries old role as expert custodians of the prized English choral tradition in a program that champions the music of English composers as well as works by Gabrieli. Grandi, Duruflé, Lauridsen and Stravinsky. The tourists also pay homage to their hosts with a world premiere performance of Charlotte, a 2023 composition by Australian composer and multimedia artist Damian Barbeler to words by Judith Nangala Crispin, a Canberra-based poet and visual artist.

The program, which brings a touch of Christmas in July, does without a pipe organ, a line-up that will change in the Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House with its grand organ. In the more intimate surrounding of the City Recital Hall, the 18 choristers with 14 adult altos, tenors and basses are accompanied by one of two chamber organists and a ten-strong brass and woodwind instrumental ensemble. The singers are well-matched and finely balanced in the hall, but missing the reverberant, floating acoustic of old stones and high ceilings, distinctive to this repertoire and to this ensemble.

Nonetheless, the choir presents a tremendously polished and finely balanced performance honed with exceptional ensemble skills. The intrinsic charm of the trebles and the purity of their voices are captivating but do not detract from their impressive musicianship, focus and stamina in undertaking a performing tour like this so far from home.

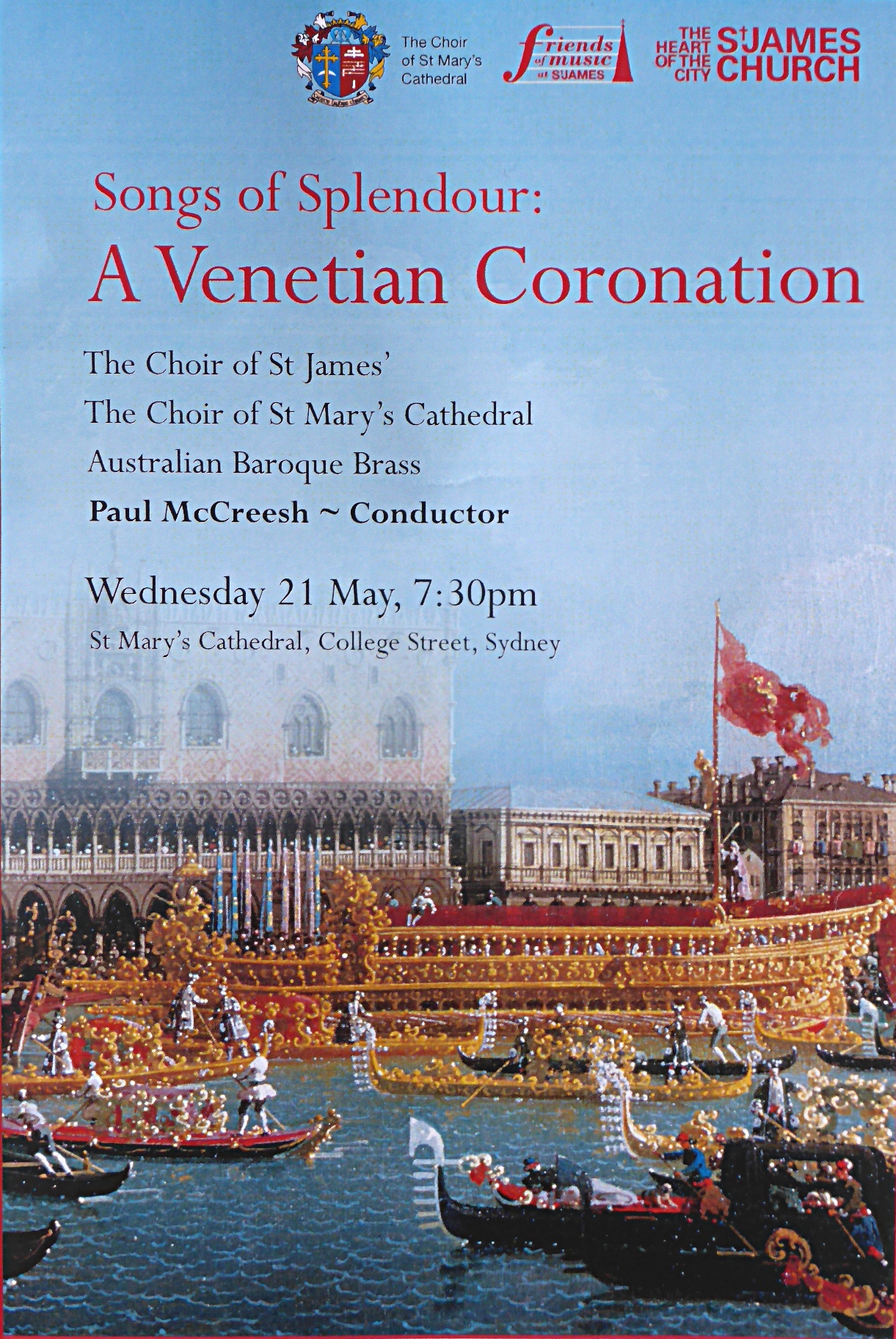

The two halves of this sumptuous program each open with a setting of the Christmas motet O magnum mysterium. Giovanni Gabrieli’s 1587 eight-part motet for two unequal choirs is accompanied by three trombones and chamber organ. Combining close antiphony and rich polyphony, cross rhythms and play with tonality thicken the textures. Much of Gabrieli’s writing was in the cori spezzati (split choir) traditions of Venice’s San Marco Cathedral with choirs achieving an echoing effect located in two opposite facing lofts. Performing as a single entity on stage the sound is consolidated into a pleasing whole. However, I did wonder how it might have sounded with the two choirs separated in some way perhaps even on stage or using the upper lofts of the hall.

The second half of the program begins with an instrumental transcription for brass and woodwind, of Morten Lauridsen’s ethereal motet of the same name by Owen Elseley. The players draw out smoothly polished lines, lingering on dissonances. The trumpet introduces the theme over the moving parts below and the woodwind takes the theme as various configurations come to the fore before the impassioned final Alleluia. There is something special about Lauridsen’s setting of the words and their absence in this instrumental transcription reminds me of the reverse process where instrumental pieces are later combined with words with varying success, namely, Elgar’s Lux Aeterna, a choral setting of Nimrod from The Enigma Variations, and Barber’s own setting of the Agnus Dei to the music of his Adagio for Strings. There are those who would propose that these come across better as instrumental rather than choral versions and this may apply to Lauridsen’s piece in reverse.

John Bull’s Almighty God, Which by the Leading of a Star is a wonderful opportunity for choral soloists to be heard alternating with choral sections, accompanied by the organ. Treble and alto take much of the imitative upper lines with the lower voices filling out the harmonies. Peppered with dotted rhythms livening the lines, the final section makes much of ascending and descending melodies, rather like an Escher staircase.

Tallis’ Videte Miraculum (1575) contains his quintessential rich but clashing six-voiced polyphony as he plays with major and minor key pivots, the treble poised above the whole as the tenor sings a cantus firmus. Alessandro Grandi’s Hodie nobis de caelo (c1610) is a short motet exquisitely sung by two solo tenors.

Maurice Duruflé’s Four Motets on Gregorian Themes comprising the popular Ubi caritas et amor, Tota pulchra es, Tu es Petrus and Tantum ergo set Latin words for different liturgical occasions. Duruflé based his motets on Gregorian Chant elaborated with polyphony, yet they shimmer with French lightness and Impressionism, sensitively conveyed by the singers who divide into smaller choirs at various points.

Damien Barbeler’s Charlotte with words by Blake Poetry Prize-winning Judith Nangala-Crispin is premiered in the presence of the writers. Performed unaccompanied, it is a dark tale of dispossession and a search for identity told through text and wordless chorus, melody, niggling dissonance and cluster chords which lament and sigh over a drone bass. Narrated in the first person, it might seem incongruous that the all-male ensemble gives voice to a tale narrated by a woman, plangently declaring “I am Judith” at the climax of the piece with its final dramatic gesture. However, it is a powerful, relevant and worthy composition.

The final three pieces, Stravinsky’s Mass (1944-8), sung in Latin and two pieces by Master of the King’s Music Dame Judith Weir, Psalm 148 (2008) and Vertue (2005), sung in English, are very different in style. They have their movements interleaved in a bold programming strategy. Stravinsky’s distinctly liturgical piece is unsentimental with little adornment, but musically complex with vivid contrasts and challenging time and key changes. The Kyrie embodies polyphonic imitation, its long vocal lines contrast with jaunty staccato in the instruments. The Gloria harks back to plainchant and the Credo is a solid chordal statement of faith. The declamatory Sanctus is followed by a jubilant Hosanna and a supplicating Agnus Dei.

Dame Weir’s Psalm 148 is unusually written for mixed choir and trombone, expertly played by Nigel Crocker. Vertue, a setting of words by George Herbert, is unaccompanied and becomes increasingly layered as the voices divide. Inspired by the styles of madrigals and hymns, it is a fortunate introduction to the music of this contemporary British master whose music is rarely heard in the Antipodes. It would have enhanced the understanding of the piece had the text been printed in the program.

Bravo to Daniel Hyde for respectfully requesting that applause for the last two pieces be withheld until the very end of the Mass. All too often, the continuity and mood of carefully curated pieces, is broken up by distracting gaps for applause and bows or commentary. The uninterrupted performance of short brackets of pieces is much appreciated and is a practice that could even have been applied to the first few pieces on the program and should be more widely adopted by ensembles in Sydney

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©