In Conversation With Dame Emma Kirkby

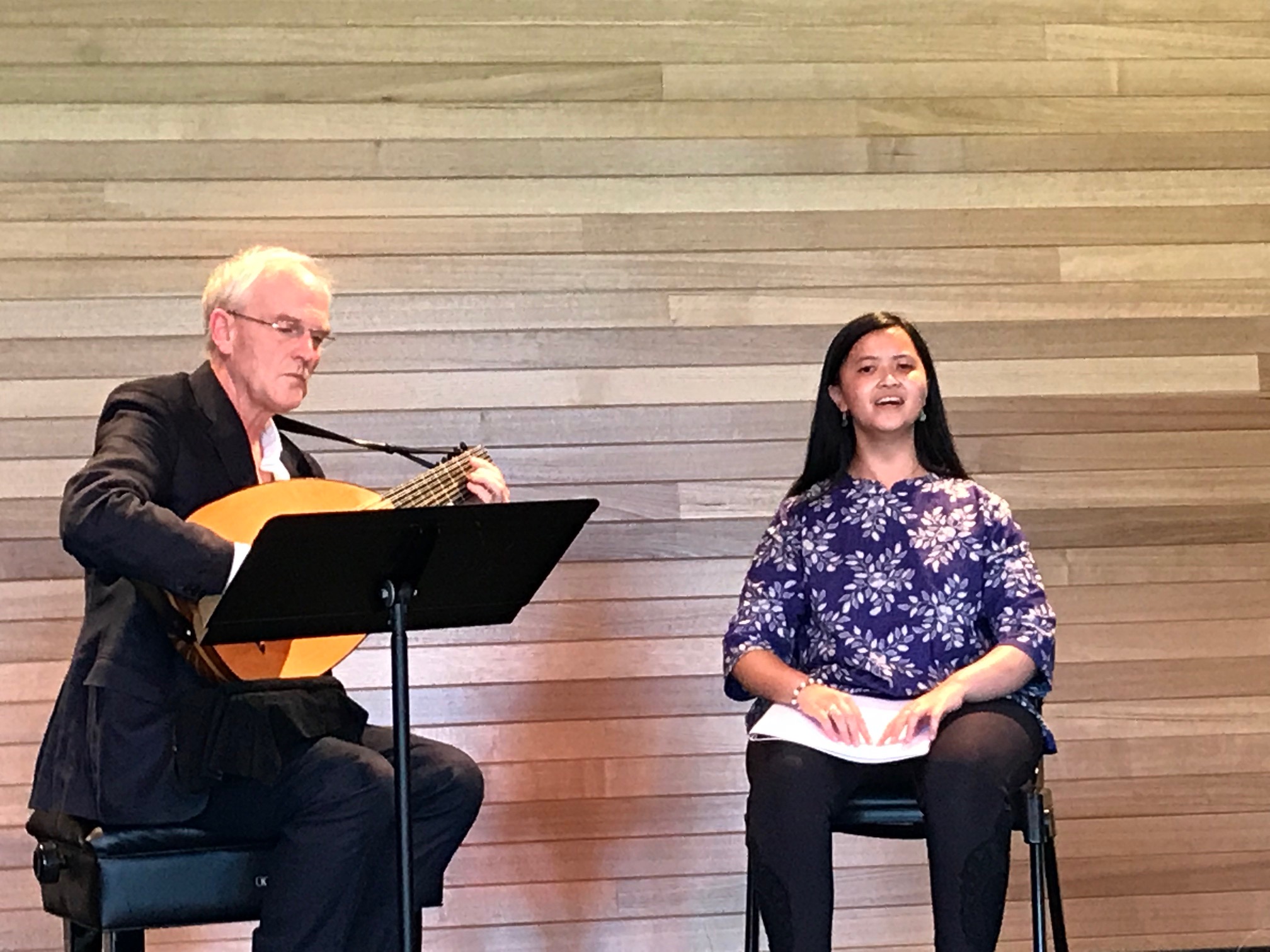

British soprano Dame Emma Kirkby and Swedish Lutenist Jakob Lindberg were recently in Australia performing and running masterclasses. During their tour, the duo were in Bermagui, where they presented a masterclass on The Art of Performing and Understanding Early Songs as part of the Four Winds Windsong series.

SoundsLikeSydney correspondent soprano Ria Andriani attended the masterclass renewing her friendship with Dame Emma, with whom she has also had masterclasses in the UK. During the weekend, Dame Emma agreed to an interview with Ria when they discussed voice types, English musical traditions, performance boundaries and of course, the inspiration behind her recital program.

RA: What’s your opinion on the perception that early music should be performed with ‘straight’ tone?

EK: When I’m working with singers, I try to meet them where they are and help them make the little changes which enable them to embody the emotion in the music. Having the right accompaniment such as a lute for 17th century music, or obbligato instruments for a Bach aria does go such a long way towards getting the right vocal results and helps with the delivery. Unfortunately, nowadays we use the piano for everything, and sometimes it doesn’t have the subtlety or the dynamic range to suit early music.

RA: What’s your opinion on vibrato? Is this something that should be avoided in early music?

EK: when you’re working with a lute, or with a few instruments in an intimate chamber setting, their sound disappears into silence, leaving so much space and freedom for the singer to ornament. Vibrato in itself is a highly-prized ornament which the human voice could choose to do, but it wasn’t the basis for the vocal technique of the time because we had a different sound world created by those instruments. What is more important is the delivery of the text. When you sing good consonants on ringing notes, your voice warms up and the vibrato will come naturally.

RA: There’s a perception that vocal music before 1759 speaks, and after that it sings. Do you agree?

EK: It’s an interesting idea. Certainly, the vocal line at the end of the 18th Century becomes more decorative and the text is fluffier. That’s why I love working with lute songs because it is just one notch up from speech. Even when you have lots of verses, they are different from the one before.

RA: Where did English composers vanish after Thomas Arne and Henry Bishop?

EK: There were composers who continued the tradition like William Jackson of Exeter, Robert Lukas Pearsal and Henry Hugh Pierson in the 19th Century. Pierson spent most of his time in Weimar, Germany. When he presented an oratorio as part of the Norfolk and Norwich Festival, the reviewers who came from London were so disparaging about the “upstart” that he went back to Germany where he was admired and appreciated. Then there’s Sir Arthur Sullivan who was such as good composer as well.

RA: There’s a quote from Dame Isobel Baillie, the Scottish soprano that ‘you shouldn’t sing louder than lovely’. Comment?

EK: That’s absolutely right. More research needs to be done into how musicians use performance space. A potent example is the trio in Mozart’s Mass in C minor. Traditionally, it has been performed with the two sopranos to one side of the conductor, and the tenor on the other side. It’s full of sixteenth notes and really difficult to hear each other in that configuration. But if you put the tenor between the sopranos, then it becomes a true trio and you’ll find it is easier to sing those sixteenth notes as ornaments – which they are.

RA: Do you have any boundaries as to what you would or would not perform? For instance, the role of Dido in Purcell’s ‘Dido and Aeneas’ has a precedent for a powerful portrayal set by Dame Janet Baker?

EK: I am too much of an anarchist to allow one interpretation of a role. In terms of the vocal range, Dido could be sung by a mezzo-soprano, or a soprano. If someone has the voice, fine sensibility and is able to embody the emotion, then their performance is equally valid.

In terms of what I would do, I’ve always explored whatever falls into my lap so I rarely say “no”. However, once I was asked to sing for a performance of Verdi’s Requiem in a small church. I declined because my voice wouldn’t work out with the setting and the space.

RA: When was the last time you came to Australia?

EK: In 2005 with Antony Walker, Cantillation and the Orchestra of the Antipodes. I love working with Antony Walker because he’s brilliant and always has something new to say.

RA: What are you doing on this current visit?

EK: I am enjoying performing in three different venues: the Melbourne Recital Centre, which is quite big and yet so intimate. Right now, we’re in the intimate space of the Four Winds Pavilion in Bermagui which barely fits a hundred and then there’s the Utzon Room at the Sydney Opera House with its gorgeous backdrop of the ocean.

RA: What is the inspiration behind the pieces you’ve put together in this programme?

EK: The first half is a journey towards John Dowland via two other very interesting composers: Robert Jones and John Danyel. The second half is influenced by John Dowland’s son, Robert Dowland’s Musical Banquet 1610 in which he collected various songs from different countries in Europe. Its choice is also spurred by the grief many of us feel by the thought of Brexit. Jakob will also play some lute solos, because it’s important when you’re performing with a very fine accompanist to let them be heard on their own – it is their moment too. I hope we’ll see more of that collaboration even in the later repertoire.

Ria Andriani for SoundsLikeSydney©

Ria Andriani graduated with Bachelor of Music/ Bachelor of Arts from UNSW in 2015. She now sings as a soprano with various choirs in Sydney, and presents recitals in collaboration with other musicians. Follow Ria on www.facebook.com/RiaAndrianiSoprano