Opera Review: Anna Bolena/ Opera Australia

Anna Bolena – Donizetti/Romani

Anna Bolena – Donizetti/Romani

Opera Australia

Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

2 July 2019

Written by Victoria Watson

Bel canto opera is best known through the works of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, written in Italy in the early 19th century. This was a second flowering of the “bel canto” (beautiful singing) concept however, with the beginning of opera around 1600 being the first. These early Baroque composers focussed on the power of expression of the solo voice which was linked to dramatic developments in the teaching of singing and resultant extended technical and expressive skills for the human voice in western art music.

Anna Bolena, Donizetti’s first major success, was written in just one month for the great soprano Giuditta Pasta to sing in Milan in 1830. His famous rival Bellini premiered his La Sonnambula three months later.

Opera Australia presents a new production of this opera, never presented before by the national company. It is led by Italian director – choreographer Davide Livermore who also directed OA’s Aida, which introduced the ten giant LED screens that will feature throughout OA’s 2019 season and beyond.

As has been seen in Aida and more recently in Graeme Murphy’s new Madama Butterfly, the screens are new technologies driving artistry, not unlike the evolution of stage machinery in the Baroque era that saw the scenic designer gain top billing over the singing stars and the composer. Parallel to that moment in history where new technology dominated the stage, the artistic dangers are rife with the music and drama being very easily overwhelmed by the sheer brightness and dominance of the screens. Much of the responsibility for this falls to the digital entertainment company D-Wok which worked with the creative team on the digital content. This production does not fully solve these balance and artistic issues, but there are some more successful integrations of the new technology than those seen in Aida or Butterfly.The panels, the integrated physical set and a double revolve all move fairly constantly and are rather at odds with the more static conventional approach to the acting style. Also the incessant movement created considerable distracting stage noise over softer musical sections of opening night. There were also many problems with lighting, and characters were often singing in total darkness or excessive shadows. Hopefully, this will be improved during the season.

Where the designs did not serve the story well or dwarfed the performers, they did not serve the art they seek to enhance. The imagery throughout of a hawk, representing the house of Anne’s family and perhaps her captive state and Henry’s aggressive hunting for a mate, were successful in part, though a little overplayed in the dancer sequences. As is the fashion in modern opera production, the overture was a fully choreographed and digitised affair. The gawky humour seemed at odds with the music and the story to follow, and the presence of the ubiquitous Smartphones and selfies were particularly jarring. The digital images of London being built and unbuilt also beg the question of relevance and seemed to be telling a different story to the opera.

There were standout performances among the singers. Anna Dowsley portrayed the pants role of the doomed admirer Mark Smeaton with great flair and panache. Her voice displayed true bel canto fineness of tone, clarity of pitch and fluid coloratura with affecting dynamics and phrasing. Her portrayal was physically convincing and her authentic empathy for the character elicited a sympathetic response in the audience.

Also in fine form in minor roles were two other Australian regulars, tenor John Longmuir as Hervey and bass Richard Anderson as Anne’s brother. It was difficult to understand why these three fine Australian artists so at home in this repertoire vocally and dramatically were not featured in larger roles which they would have performed with great success.

The chorus performed particularly well in muted sections for female and male voices, separately achieving a hushed grandeur that enhanced the drama. The orchestra was less even and tempi fluctuated erratically throughout the evening under conductor Renato Palumbo. The horn section had a number of unstable moments and the slowness of some numbers created a lack of forward energy in the score at times.

In the four central roles, bass-baritone Teddy Tahu Rhodes was the least convincing vocally. While his voice is strong and audible, it has developed an indistinctness of pitch and diction that makes it much less suited to bel canto repertoire. He was at his best singing lightly in the ensembles. His characterisation was gruff and violent and lacked the subtlety or softer romantic aspects that may have balanced this unlikeable portrait of Henry VIII.

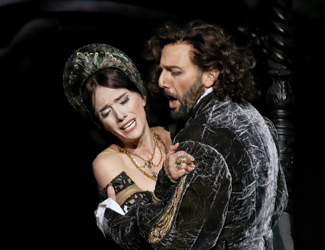

Italian tenor Leonardo Cortellazzi was well suited to the role of Percy, Anne’s first betrothed who is brought back to court by the King in a plan to rid himself of his second wife and replace her with Jane Seymour. He is handsome and fervent with a pleasing tone that handles the demands of the role with aplomb.

Romanian mezzo-soprano Carmen Topciu is new to Australian stages and has a rich voice of size and flexibility. She is moving to Verdi roles in her career and will do very well in that repertoire. In this opera, Jane Seymour is ‘the other woman’, consumed with her passion for the king, against her loyalty to her friend the queen. A depth and complexity of emotional range to portray this internal conflict is at the heart of this opera’s success, as is a convincing sensuality and chemistry with the king. On opening night this was not fully achieved in Topciu’s characterisation and vocal performance. There was a more stolid approach, while very secure musically and vocally, she displayed a limited emotional range.

Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho has the greatest weight on her shoulders in this opera created by Donizetti for the greatest soprano of her day – the diva Giuditta Pasta. Renowned for her verismo heroines and her affecting Traviata, she seems a sure thing to portray the spurned Tudor queen. However, this is bel canto opera, not verismo, and intensity alone will not win the day. In the softer singing requiring a melting “morbidezza” tone, Jaho is a supreme master and at her very best. The final “mad” scene is a great success as a result of this great skill. The characterisation was focussed on tortured anguish, which began very early and lacked contrasting states to fully explore the rich possibilities of the role. In her louder singing Jaho exhibits physical tensions in the neck and frame which create a less pleasing vocal tone than suited to the melodic demands of bel canto song. There is an edge and pitch fluctuation which can mar the musical beauty. Her histrionic gifts were exploited to the full by the director, but it was only in the final scenes that her command of sotto voce singing won true sympathy for the woman behind the crown.

SoundsLikeSydney ©

Victoria Watson is a graduate of Melbourne university and VCA. She appeared regularly as a soprano with the Victoria State Opera and has toured and served as artistic director of many chamber ensembles.

She has performed with Sydney Symphony Orchestra and for ten years, was artistic director of a major opera education project with Opera Australia. Since 2015 she has moved into directing opera including Mozart’s Cosi Fan Tutte at the Independent theatre.

Victoria has lectured in voice at the major universities in Melbourne, and is currently a tutor at UNSW. Having taught at major Sydney secondary colleges, she now runs a busy private singing studio. She is a published author on opera and a popular freelance music and theatre lecturer and advocate for Australian artists around the world.